Drive two hours north from Philadelphia, where Cait teaches, and you will find yourself in the town of Scranton, Pennsylvania. It’s a midsized, handsome but not especially wealthy town, with an industrial past. It might seem a strange place to begin a story of dignity — but America’s evolving economic mores can be observed through its history.

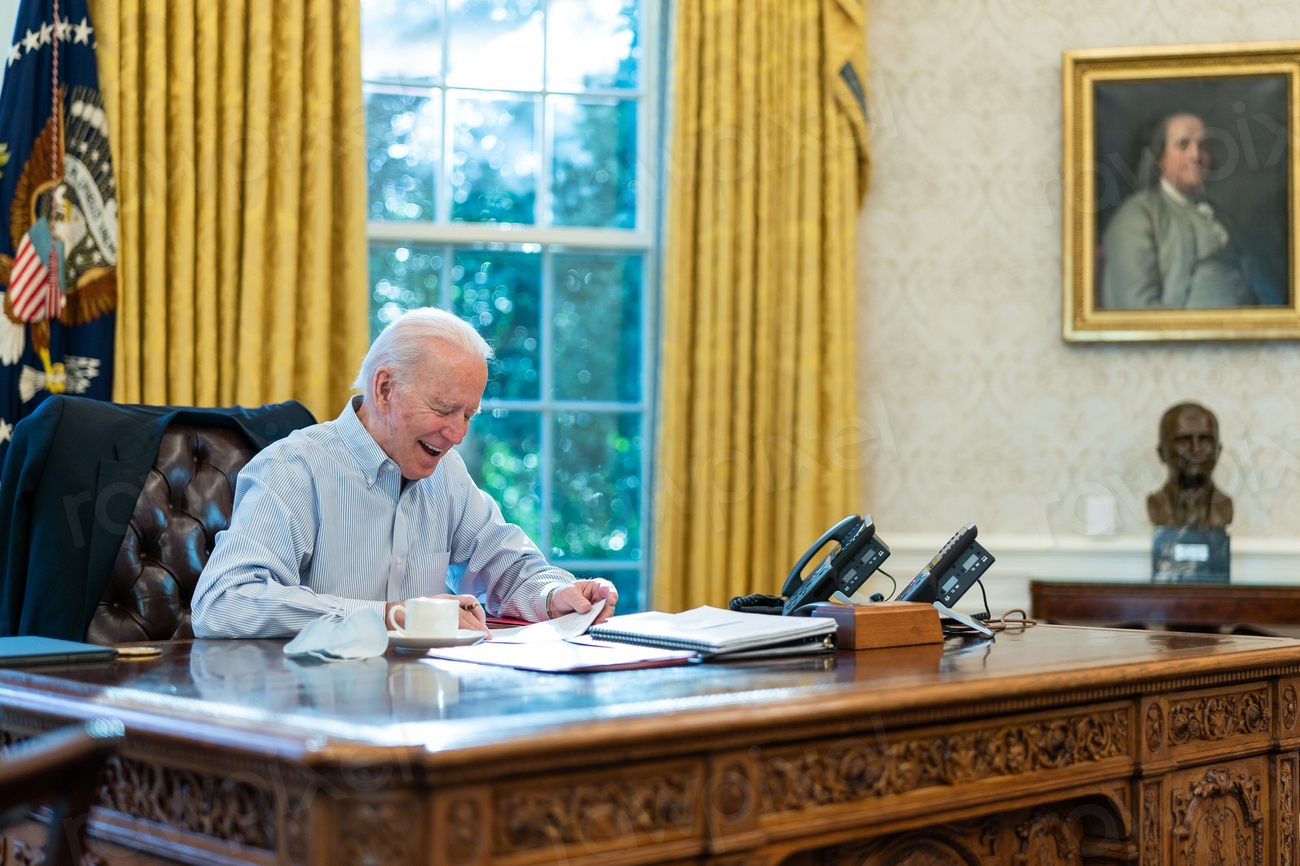

The town’s most famous son is President Joe Biden. In his memoir, he doesn’t offer strong recollections of favorite teachers. Neither the nuns who staffed St Paul’s primary school, nor his football coaches, nor the speech pathologist he saw for his stutter, seem to have made him feel seen in the way a young boy might have hoped. In fact, one of the most moving recollections in his memoir is of the unnamed sister who once mocked his speech impediment — his fury at that moment clearly still burns. Instead, feeling seen, and respecting others, seem to have been things that he found in his family: his mother insisted that he pay no heed to rank, even when meeting Queen Elizabeth or the Pope — “Remember, Joey,” she’d say, “you’re a Biden. Nobody is better than you. You’re not better than anybody else, but nobody is any better than you” (Biden, 2020).

That ethic seems to have been complemented by the types of businesses and economic relationships he came across in Scranton. The businesses he visited were places where he knew the owners, often well: even though he left Scranton behind at the age of ten, he still recalls shopping at Handy Dandy, Pappsy’s, Simmey’s, Joseph Walsh’s insurance agency, and Mr Thompson’s market. The world he recalls is one in which these young boys could explore town, known by neighbors and business owners who would keep an eye on them. In fact, it’s exactly the sort of world recalled by Jane Jacobs, the urban theorist, who was herself born in Scranton. Her great work, ‘The Death and Life of American Cities’, with its calls for residents and store-keepers in mixed-use neighborhoods to keep an eye out for one another, was profoundly influenced by her experience in Scranton, as the historian Glenna Lang has shown (2021).

One shop Biden doesn’t mention is Woolworths, though Scranton is proud to be the home of the chain’s first successful store, which opened in 1880. Perhaps that’s because by the time Biden might have visited in the 1940s, the chain of ‘five and dime’ stores had already come to symbolize the standardized capitalism that discouraged human relationships. Consistent at scale, paying little and with a relentless focus on efficiency, Woolworths was an early example of some of the trends that came to dominate American business. Yet the history of Woolworths also reminds us that this very standardization began as a respectful step forwards for business. Former Woolworths UK employee Paul Seaton relays the following story from the founding of the store:

“In later life Frank Woolworth recalled a particularly formative moment in his teenage years. He and brother ‘Sum’ saved up their nickels and dimes to buy their mum a birthday present. As the day approached they headed off into town to look for something. They toured the centre of Watertown…in search of a gift. They settled on a scarf costing 50¢. When they came to pay, all in loose change, the assistants all gathered round to snigger. The poor boys were teased that in a year’s time they would have scraped together enough cash to buy the other half of the matching gloves. Frank recalled the humiliation and hated the way poor customers were treated so badly compared to richer people. He walked out and bought from another store. On the way home he told Sum that one day 50¢ would be enough to buy five or ten items, and every customer would be treated with respect. It was an important learning, which later inspired one of the stores’ core values. Woolworth’s aimed to be ‘classless’ and to give the same friendly, efficiently service to everyone, whether they were spending a little or a lot.”

That basic human respect might have aimed to be classless, but it was not colorblind. Woolworths’ lunch counters permitted black customers to sit only after the brave efforts of protestors. Scranton has its own history of civil rights protests from Black would-be customers demanding an end to state and corporate discrimination. Local historian Glynis Johns holds up businesswoman Louise Tanner Brown as an early local heroine to the town’s small Black community. (Many of those Black-owned businesses were displaced in the 1970s by Scranton’s new malls, in exactly the sort of faceless attempts at urban renewal that Jane Jacobs fought against).

Another thinker, born just outside Scranton, was the psychologist B.F. Skinner. His book ‘Beyond Freedom and Dignity’ argued that scholarship need not pay too much attention to people’s inner lives. Perhaps he should have stayed in Scranton a little longer, and observed the human liveliness that Jacobs and Biden describe. That common desire was summed up in the immortal words of Scranton’s most famous fictional resident, The Office’s Michael Scott: “Respect. R-E-S-Pee…Svee-Tee!. Find out what it means to me.”

On the campaign trail, Joe Biden talked frequently about dignity. “Everyone’s entitled to dignity,” he said, “That’s a basic tenet in my household.” After his election, addressing the UN General Assembly, he affirmed “I am not agnostic about the future we want for the world. The future will belong to those who embrace human dignity.” His repeated focus on his own inner emotional experience of dignity and grief, and that of his constituents, is a sort of refutation of Skinner. Biden’s ideas have begun to translate into policy, with a newly reactivated Consumer Financial Protection Bureau focused on understanding and protecting people’s financial lives, and the administration’s Competition Council taking initiatives to create a ‘right to repair’ and protect people of all identities from discrimination by businesses.

Even those of us who don’t know Scranton, know a town like it. We all have relationships in our lives that are human as well as economic, and we know the value they carry. Isn’t that something you would want for the customers you serve too?